Japan’s world-renowned cuisine reflects its storied history—don’t leave the country without trying these foods.

Japan has a proud and rich history surrounding its cuisine. Kyōdo ryōri, or regional dishes, dominate menus as you move throughout the island nation, where a rotating showcase of plates is powered by a bounty of shun no mono (seasonal ingredients). And then there’s always the regional take on sake to accompany it, called jizake when brewed locally.

Traditional Japanese cuisine even has a special name, washoku, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. That complex and diverse gastronomy is owed, in part, to the geography of the country, which affords it access to edible riches from both the land and the sea. Seafood—and sea vegetables—are readily plucked from the ocean, while the earth is cultivated for staples like rice and soybeans. Incorporating a wide variety of seafood and vegetables, as well as fermented foods like pickles or miso soup (known for their probiotic health benefits), Japanese cuisine is traditionally low in fat and high in nutrition.

In Japan, the cuisine is about not only what’s on the plate but also how it’s presented. It’s often said that Japanese people eat with their eyes, and a traditional meal will often include five colors; it’s believed this magic number guarantees that the body will get a nutritious meal.

The History of Japanese Cuisine

In 675 B.C.E., the Japanese emperor, Temmu, passed a law that prohibited the consumption of mammalian meat for religious reasons. For 12 centuries, the island nation enjoyed a pescatarian diet rich with vegetable dishes. During the Kamakura period (1192–1333 A.D.), shojin ryori (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine) became popular with the general public. As a result of both these historical events, the modern Japanese diet is rich in vegetables, tofu, and soy products, which can include everything from fried tofu to yuba, aka gossamer-thin sheets of soy milk. However, the most important part of Japanese cuisine (and any meal) is gohan, or rice. (Fun fact: The word “gohan” can also mean “a meal,” which reflects how integral rice is.) Modern Japanese cuisine as we know it can trace its roots back to the Muromachi period (1392–1573) when the principles of ichiju sansai (the common meal presentation of one entrée, one soup, and three side dishes) were established. Ichiju sansai is still considered a common framework for a balanced and nutritious meal to this day.

During the late Edo period (1603–1867), restaurants that specialize in one dish also became popular. Tokyo, in particular, is known for senmon ryori ten—restaurants that serve one dish such as soba, tonkatsu, ramen, yakitori, and sushi. The owner of the shop becomes a shokunin or specialist in the cuisine.

For the most part, the Japanese did not eat meat until 1872, when Emperor Meiji rescinded the prohibition. (The emperor himself ate meat, and that helped to relax society’s view.) But it wasn’t until after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, when foreign countries sent emergency rations, including canned corned beef, that the consumption of meat became accepted by the masses.

Other influences on Japanese cuisine were also imported from overseas. Chopsticks, advanced pottery techniques, tofu, tea, sushi, noodles, and much more arrived from China and Korea. Tempura is an import from Portugal, and curry from the British Royal Navy. Western Europe introduced beef and pork, and thus began the Westernization of the Japanese diet.

The Japanese pantry is based on fermented foods that are made with a mold called koji, such as soy sauce, sake, rice vinegar, and miso. Umami, the delicious fifth flavor of the palate, is an integral part of Japanese cuisine. It is naturally found in kombu (kelp, a sea vegetable) and katsuobushi (smoked and dried skipjack tuna flakes). The two are used for making dashi stock, which is the base for many dishes.

Here are 5 traditional Japanese foods to try on your next trip to Japan (or at least on your next outing to the neighborhood Japanese restaurant):

- Soba

Buckwheat has been harvested in Japan for more than a thousand years, and it was transformed into noodles, known as soba, in the 16th century. Soba is best enjoyed cold, known as zaru soba, rather than hot, kake soba, to fully appreciate its aroma and texture. Zaru soba is often served with a dipping sauce called tsuyu, which is primarily made of dashi, a popular Japanese soup stock. Don’t throw away any unfinished sauce: You can mix it with some of the hot water that the soba was cooked in (called soba-yu) to create a commonly offered savory soup to finish the meal.

Look for sobaya (soba shop) signs that say teuchi soba for handmade noodles, and keep in mind that 100 percent buckwheat noodles (jūwari) are not as common as ni-hachi, which are noodles made of 20 percent flour and 80 percent buckwheat. - Tempura

Tempura is a style of cooking in which vegetables, shrimp, and white fish are dipped into an egg and flour batter and then deep-fried. It was introduced to Japan by Portuguese missionaries in the mid-16th century, but the Japanese put their own twist on the dish by adding a special dipping sauce: a blend of soy sauce and dashi that’s often enhanced by grated daikon. The meal is usually rounded out with rice, miso soup, and pickles. - Okonomiyaki

Savory pancakes, called okonomiyaki, are primarily made of flour mixed with egg and chopped cabbage and are often enhanced with optional fillings like squid, bacon, or shrimp. At restaurants, the waitstaff will mix the customer-selected ingredients and pour them onto a teppan, a tabletop iron grill, in front of the diner. Just before it is ready to eat, the pancake is seasoned with a savory brown sauce and mayonnaise and garnished with smoky katsuobushi and aonori seaweed.

Since this dish is prepared communal-style, it’s a popular meal to share with friends and family. The dish has cultivated an especially strong following in the city of Osaka, where okonomiyaki is prominently featured on many restaurant menus. Tip: It’s hot near the iron grill, so an ice-cold beer is recommended.

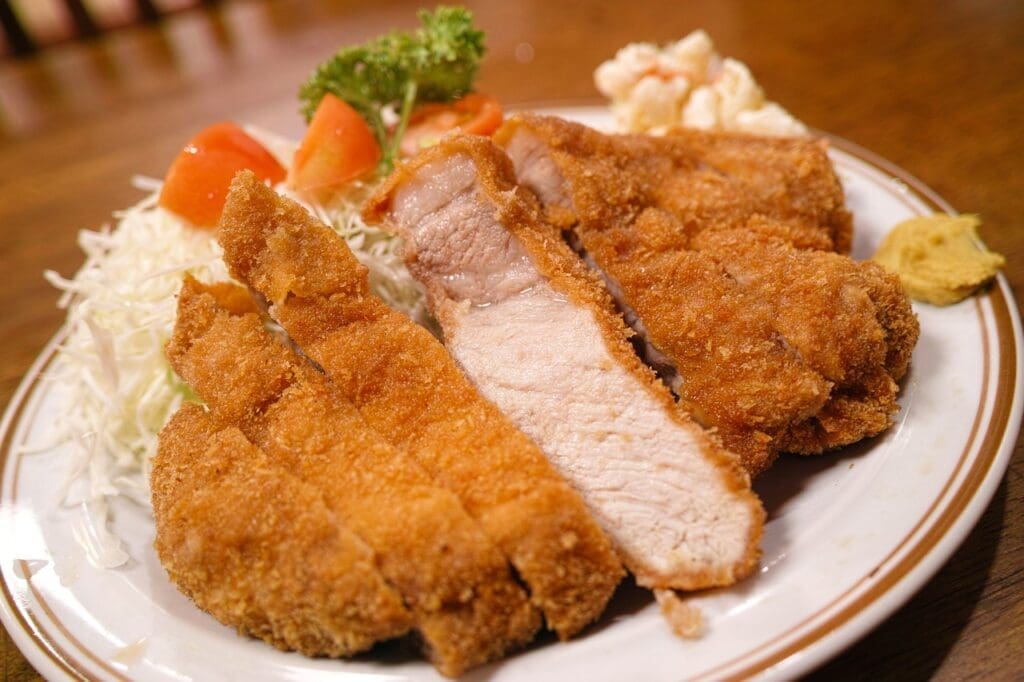

- Tonkatsu

Breaded and deep-fried pork cutlets, tonkatsu (the word comes from ton for “pork” and katsu for “cutlets”) is similar to German-style schnitzel, except instead of being cooked in butter à la Germany, they’re deep-fried in oil. Many culinary historians believe that Tokyo’s Rengatei restaurant was the first place to ever serve tonkatsu in 1895. Tonkatsu is traditionally served with julienned cabbage, white rice, and miso soup. (Bonus: Many restaurants will offer free refills of the cabbage and rice.) Not a fan of pork? Swap it out for variations of other ingredients that can be similarly breaded and deep-fried, like shrimp (ebi furai) or chicken (chikin katsu). - Wagyu

Marbled Japanese beef, called wagyu (wa means “Japanese” and gyu is “beef”), comes from four cattle breeds that are raised throughout Japan, with popular breeds like Kobe beef, Matsuzaka-gyu, and Hida-gyu. The marbling itself is called shimofuri and makes for tender cuts of beef that melt in your mouth.

Sukiyaki, created in the late 1900s, is one popular dish that features wagyu, sliced thin and cooked in a cast-iron pan on a portable tabletop grill, along with vegetables and tofu, in a sweet soy broth. The finishing touch is a coating of raw egg, which is brushed on just before being served.